Estate Planning Checklist for New Parents

By Attorney Patrick Nolan

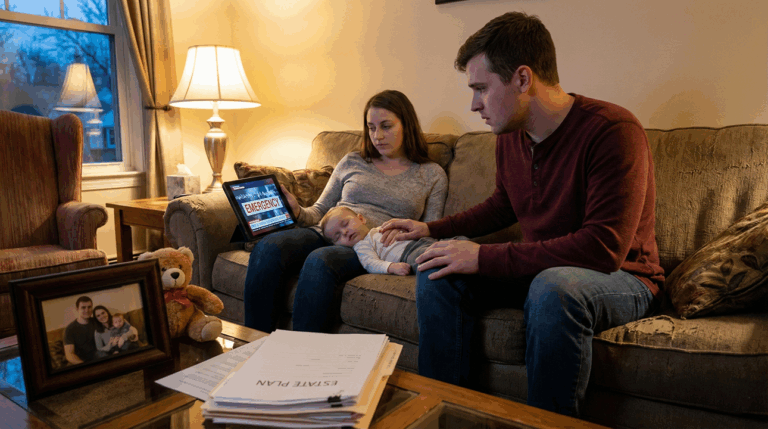

New parents don’t usually think about estate planning until something scares them into it—a news story, a close call, a friend’s emergency. But once you’re responsible for a child, the question shifts. It stops being about documents and starts being about who steps in if you can’t.

Estate planning for parents isn’t paperwork. It’s problem-solving. It’s making sure your child doesn’t get caught in a system that wasn’t built to know them, love them, or raise them. The documents only matter because they force the decisions.

Here’s how the pieces fit together.

I. What Happens to Your Kids if Something Happens to You

A child can’t inherit in their own name. The law freezes everything until a judge steps in. That’s why parents need two things right away: a guardian and a trust. Without them, you leave a mess that lands squarely on your child.

1. Naming a Guardian

You put this in your will because that’s where a judge looks. It doesn’t matter whether you built a trust or not—the will is the tool the court uses to transfer legal custody.

A guardian is your “backup parent.” Somebody who can walk into the child’s school and pick them up without a police escort. Someone who can give them stability while they’re still sorting out the shock of losing you. If you don’t name one, the system fills the gap. It’s never gentle.

2. Leaving a Trust Instead of a Lump Sum

Leaving money outright to a child is an invitation for court oversight and potential disaster. A trust prevents that. It holds the inheritance until your child is old enough to use it without blowing it or having it siphoned away in a divorce later.

You pick the trustee—the adult who manages the money. You decide when the child gets control. Twenty-five. Thirty-five. In stages. Or never outright at all, letting the trust protect the money their entire adult life.

You also give the trustee power to spend money for the child’s needs—school, health, life basics—before the trust ends. That’s how you make sure college still happens even if they’re too young to “receive” anything yet.

II. If You’re Alive but Incapacitated

This part makes people uncomfortable, so they avoid it. But incapacity is more common than death for young parents. A wreck, a stroke, an illness—you don’t need to die for the gears to lock up.

Two documents carry the load here.

Financial Power of Attorney

This appoints someone who handles your money if you can’t: banking, real estate, bills, business decisions. Without it, your spouse or family might have to file a guardianship just to sell a car or access an IRA.

Healthcare Documents

You name someone who can speak to doctors, get your medical records, and make decisions when you’re unconscious or unable to communicate. This also includes your end-of-life instructions—the scenario everyone avoids talking about until it’s too late.

You document it so your family doesn’t carry the guilt. Or fight each other.

III. How Your Estate Actually Moves

People assume their will controls everything. It doesn’t. Assets move in different lanes, and you need those lanes pointing in the same direction.

Choosing Your Structure: Will or Trust

A Revocable Living Trust is the cleanest way to bypass probate, but it only works if you transfer assets into it while you’re alive. That’s the part people skip, and it’s why so many “trusts” fail.

If you use a trust, you also sign a Pour-Over Will—a safety net for anything still in your name when you die. It sends those leftovers into the trust, but those leftover assets still go through probate.

Fixing Your Beneficiary Designations

Retirement accounts, life insurance, and certain financial products don’t listen to your will. They listen to the beneficiary form. If you name a minor on one of those forms, the court gets involved. If you name a trust but the trust wasn’t built for minors, you cause a different mess.

Get the designations consistent with your overall plan.

IV. The People You Choose to Run the Plan

Someone has to carry the ball when you’re gone or incapacitated.

Naming Fiduciaries

- The executor (for a will)

- The successor trustee (for your trust)

- The agents under your financial and medical powers

- Backups for every role

People age. People move. People burn out. This is the part families most often get wrong because they assume the person they love is the right person for the job.

Sometimes that’s true. Sometimes it’s definitely not.

V. Pulling It All Together

Organize What You Own and Tell People Where It Is

A plan only works if someone can find it. Create an inventory—accounts, debts, logins, assets. Keep it in a secure vault or binder. That simple step saves months of confusion later.

And talk to the people involved. Don’t leave them guessing. Tell your guardians what you expect. Tell your trustee how you see the money being used. Tell your agent why you picked them. It’s not a ceremonial conversation; it’s practical.

You’re giving them the ground rules before they have to play referee in a crisis.

Estate planning isn’t about documents. It’s about clearing the path so your child never has to stumble through a legal maze when they’re already carrying enough.